The Dead We Know Best

The Past Is Not Distant. It Is Simply Waiting.

I’ve been reading Ian McEwan’s remarkable new novel, What We Can Know, and I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it not just as a reader, but as a writer of historical fiction. The book is set a century from now, in a Britain partially reclaimed by the sea, where a scholar named Tom Metcalfe has devoted his entire working life to reconstructing the story of people who lived in our own era: this moment, right now. To do it, he reads their emails, their journal entries, social media posts, texts, interviews, and their scribbled notes. He pieces together who they were from the fragments they left behind.

Sound familiar?

McEwan’s central preoccupation in the novel sits at the very heart of what historical fiction writers do every day: what can we actually know about the people of the past? And beneath that question lies something even more unsettling — that we may know certain people from history more intimately than we know most of the people in our own lives today. Tom, spending years immersed in the letters and private correspondence of Francis and Vivien Blundy, comes to carry them with him like the weight of old friends. He understands their marriage, their fears, their tenderness toward each other, in a way that defies the century between them. The past, McEwan suggests, is not distant. It is simply quiet.

I felt that recognition viscerally, because I have lived it.

When I first approached writing a historical fiction novel based on an ancestress’s diary fragment, my biggest challenge wasn’t the prose. That came later, in all its glory and grief. No, for me, it was establishing which parts of the work would be truth and which I would dare to fictionalize. After re-reading some of my favourite historical fiction writers such as Hilary Mantel, Jean Plaidy, Anya Seton, and Margaret George, I felt I had a reasonable handle on how to navigate those turbulent waters. What I didn’t want, more than anything, was to fabricate facts to serve my fiction. Even with the forgiveness of an author’s note.

So: truth based in fact, and dare to be bold in interpreting emotions, motives, and outcomes. That became my working rule, and I scrutinised my writing against it every day.

Going a step further, I decided to approach my research from two perspectives. The first was immersive. I read any fiction and non-fiction book that caught my eye and seemed relevant to the period. I was fairly widely read in the preceding sixteenth century, but most of the action in The Lady of the Tower takes place in the seventeenth century. I needed to brush up on my Stuarts. This involved a voracious consumption of the driest textbooks (try Divine Right and Democracy: An Anthology of Political Writing in Stuart England for an evening of light reading) alongside the wonderful biographies of Antonia Fraser, Anne Somerset, Paul Sellin, and Roger Lockyer. I decided early on not to read too much fiction set in this time: I wanted to develop my own voice, clearly state my own interpretation of those times. Well, OK, guilty pleasure - who could resist reading Forever Amber again (probably the first time since a teenager) in the name of research!

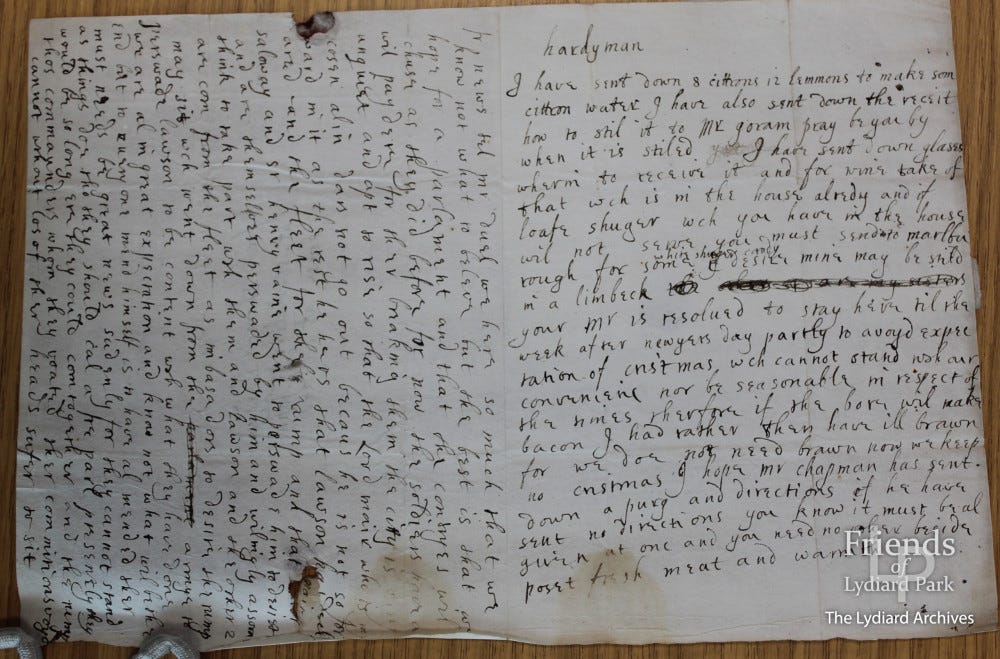

What fascinated me most were the footnotes, because from them emerged the original source documents. That was my second methodology: going deep into the contemporary records. Subscribing to British History Online and the National Archives opened up the world of digitised manuscripts, and Google Books unlocked the Calendars of State Papers. Now I was truly humming. The hunt was on for every single character who would appear in my book, and the riches provided by these online sources were extraordinary — letters, pleadings, court appearances, dispatches. Some were written by my characters; others merely mentioned them in passing. Each one provided a clue to the personality and motivation of these people I was slowly, carefully, coming to know.

And this is where McEwan’s insight cuts so close to the bone. His scholar Tom pieces together the lives of Francis and Vivien Blundy the same way I pieced together Barbara and Eleanor and the others who populate The Lady of the Tower: through the accumulation of small human details. A turn of phrase in a letter. A choice made in a moment of crisis. The way someone signs off their correspondence. Reading their own words, or speeches transcribed by clerks, I could begin to plot their character arcs. I could start to understand why one married another, why Barbara would always be a survivor, and why Eleanor was such a sweetheart.

McEwan writes of the strange intimacy that forms between a researcher and their subjects, this sense that people separated from us by time can feel more knowable than our own neighbours. I understand that completely. During the years I spent with the women of The Lady of the Tower, they became more real to me than many people I encountered in the living world. I had access to family portraits, and as I wrote, I chose desktops and rotating images to keep them constantly before my eyes. Each day, their voices grew more insistent. The research receded into the background as a foundational layer of solid, accurate fact, and my imagination was finally free to take flight above it.

There were practical discoveries, too, of course. I still didn’t know how long it would take to ride from Swindon to Castle Fonmon, or what the route would look like, or what my heroine would have seen along the way. This is where Google Maps became unexpectedly miraculous: sitting at my desk in California, I could drop into a footpath in Wiltshire and know exactly what the land looked like beneath her horse’s hooves. The digital age has given historical fiction writers tools that our predecessors could only have dreamed of. Now, AI research tools have joined the arsenal too, allowing for even faster cross-referencing of obscure archival sources, though I’ll confess nothing quite replaces the visceral thrill of pulling up a hand-copied State Paper and finding your character’s name staring back at you from four centuries ago.

More than anything, I felt I owed it to my distant family to bring them to life in an account that retained the atmosphere of the time without making the writing too inaccessible to the modern reader. This is where, after several false starts, I determined point of view (first person) and a register of language that would appeal to my potential audience. I knew I wasn’t writing romance, though love stories are threaded through the book, and I didn’t want twenty-first century attitudes creeping in uninvited. I settled, eventually, on Jane Eyre as my touchstone. Although written a couple of centuries after the period of The Lady of the Tower, I felt that its sentence structure conveyed a sense of an earlier world, while the restrained passion in the writing and the heroine’s character made her entirely relatable. Lengthy run-on sentences suffered greatly in editing, of course, but they were glorious fun to write in the first draft.

I have one confession to make. Back to the original diary fragment: I had a significant problem. Mention is made of the heroine’s first love in the following way, describing his arrival: “all the suitors that came turned their addresses to her, which she in her youthful innocency neglected, till one of greater name, estate and reputation than the rest happened to fall deeply in love with her, and to manage it so discreetly that my mother could not but entertain him…”

The problem? His name was never revealed. I had a pivotal plot point, but no character. Back out came the research, and after several weeks of digging, I found an estate — Charlton Park — close to the location of my story, and a young man, Theophilus Howard, future Duke of Suffolk, who could match the description of a hero. And then I found that two of his children later married into my heroine’s family. That, to return to Hilary Mantel’s great credo, was enough fact to establish plausible conjecture. And so “Theo” was born.

McEwan might recognise something in that moment. His Tom Metcalfe works from the same creative necessity: when documents run dry, when the record falls silent, the scholar-as-detective must reason from what is known to what must have been. That is not fabrication. That is interpretation. It is, at its best, an act of respect toward the people we’ve come to know so well, even across the distance of centuries.

What We Can Know reminds us that history is not an abstraction. It is made of people — their words, their choices, their longing and their grief. Tom Metcalfe carries the Blundys inside him like people he has loved. I carry Barbara and Eleanor and Theo the same way. We live, McEwan suggests, between the dead and the yet-to-be-born, and the dead have more to tell us than we sometimes dare to believe.

Writing The Lady of the Tower was a glorious journey. I read extraordinary books, delved into personal correspondence and private diaries, visited houses and castles and graves and gardens, and stared at portraits, silently daring the sitters to step out of their frames. During the three years it took to write, edit, and prepare the novel for publication, I came to feel that I had honoured my ancestors, and written something that brought them, finally, to life.

As I say in the book’s own summary: it may have been four hundred years ago, but they are not so different from you and me.

Perhaps that is the most important thing any of us can know.